What are pangolins?

These peculiar creatures are nothing like any other animal, and they tend to create confusion for the people who see them for the first time. On a closer glimpse, they look like a hybrid between an anteater and a pinecone, which doesn’t really help to clear the confusion. They are weird enough to have at least one pokemon inspired after a pangolin - Sandslash. These animals are highly threatened, and 15th of February has been designated as the World Pangolin Day to raise awareness about these unique animals.

Giant pangolin (Smutsia gigantea) | Author: Louise Prévot | @louiseprevot_art

Giant pangolin (Smutsia gigantea) | Author: Louise Prévot | @louiseprevot_art

Pangolins are mammals, and mammals are per definition covered by hair or fur. Some semiaquatic or aquatic mammals such as hippos, whales, and dolphins, are largely hairless, which is an adaptation to reduce drag in the water. However, pangolins don’t live in water, and they are not covered with hair like most mammals, but they are covered with scales instead. We usually associate scales with reptiles, and even though it was once thought that pangolin scales are homologous (similar duo to shared ancestry) to reptilian scales, pangolin scales have a different origin. They use their scales very effectively for defense, and when they curl up, their scales create an armor that is difficult to penetrate. The term “pangolin” comes from the Malay word “penggulung”, which means a roller, or something that curls. Although they are useful for defense, pangolin scales are a major driver of their demise, due to their use in traditional medicine.

Pangolins share a resemblance with other mammals such as the anteater, armadillo, and aardvark. However, pangolins are a distinct and unique group that belong to the order Pholidota, and their closest relatives are in the order Carnivora, that includes cats, dogs, hyenas, seals, and bears, amongst others. Together with the order Carnivora, they form a clade (a group with shared common ancestor) Ferae, whose closest relatives are the hooved mammals, such as horses and camels.

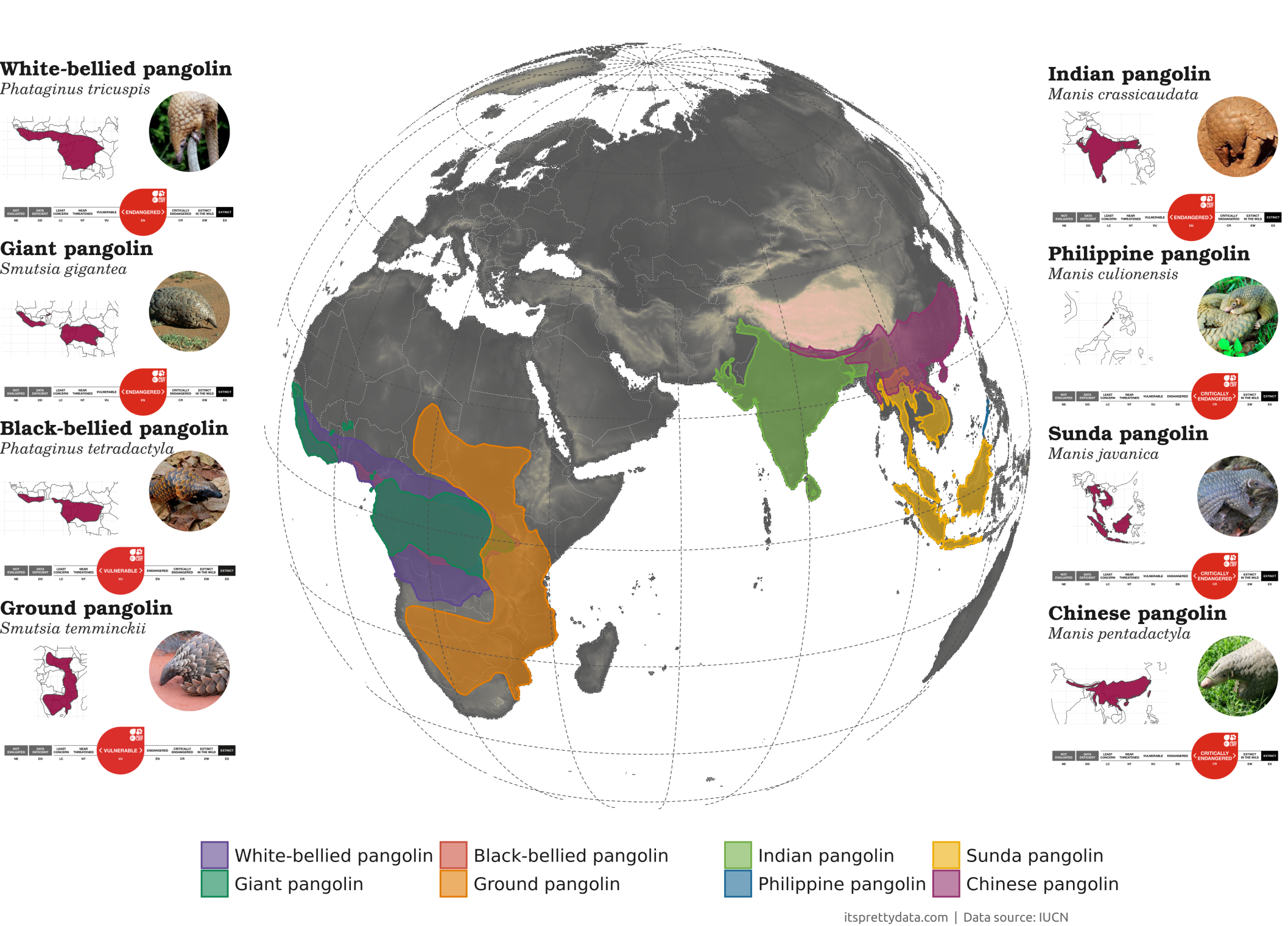

There are currently eight recognized species of pangolins. Although fossil records strongly indicate that modern forms of pangolins could have originated in Europe, surviving species today only occur in Asia and Africa. Four species of pangolins live exclusively in Asia, and the other four in Africa.

All eight species of pangolins are considered threatened with extinction. The main purpose of IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species is to assign a status that tells us how likely is it that a species will get extinct. Each species is classified into a group based on criteria such as the geographic distribution of species, population status, or presence of threats. Out of eight species, 3 are considered as Critically Endangered (CR), which is the highest threat status category that a species can have before going extinct. Remaining species are classified as Endangered (EN) and Vulnerable (VU), and species belonging to these three categories (CR, EN, VU) are considered as threatened with extinction. Threats that put pangolins under a high risk of extinction are mainly overexploitation, and habitat destruction.

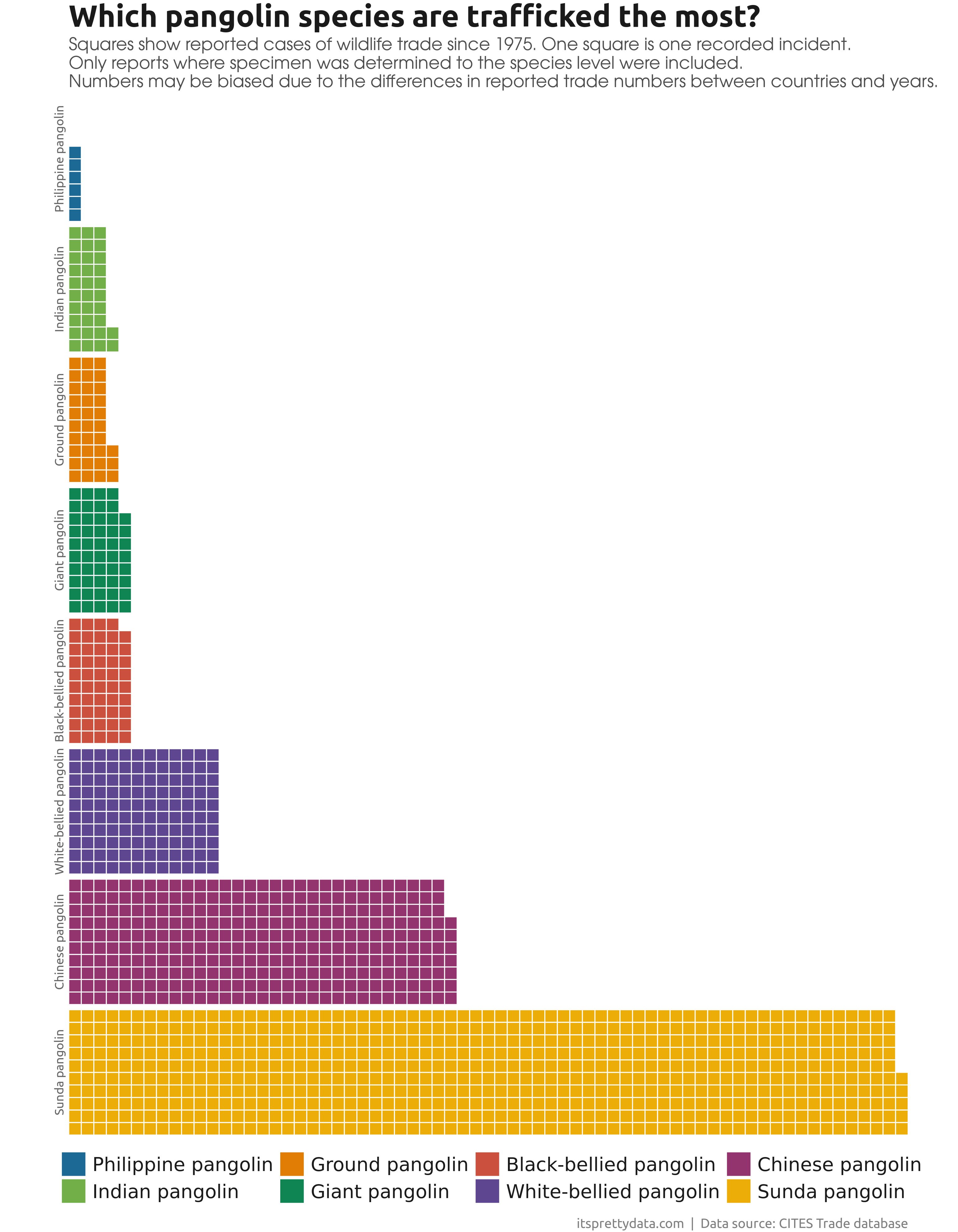

The most trafficked animals in the world

By far the largest threat for pangolins is overexploitation in wildlife trafficking and hunting. Their meat is used for food, and their scales are used in medicinal purposes, as it is believed that they can heal various ailments, anything from digestive problems, reproductive diseases, to mental issues. These claims led pangolins to become the most trafficked animal in the world, with over a million of pangolins estimated to have been trafficked in the last decade. However, claimed medicinal benefits of pangolin scales have never been confirmed, and the scales are made from keratinous material which make them no different from human nails.

When pangolins curl into a ball to defend themselves from the attack, their scales create a shield that can be impenetrable even for a lion. However, curling up into a ball is not an effective defense strategy against humans, since we can easily pick them up with our hands. This makes pangolins a very easy and profitable target for hunting.

Even though pangolins were once used as cheap bushmeat, they are now becoming much more of a commodity in parts of the world, mainly in some Asian countries. One kilogram of pangolin scales in China can cost up to 1300€ (1400$), and the price for a kilogram of meat can go up to 300€. Considering that the purchase price for a kilogram of pangolin scales in Nigeria can be around 5€, the profits from pangolin trade can be enormous, which is driving an entire illegal industry of wildlife trafficking. Despite the high price, the demand for pangolins is greater than the supply, which is rapidly driving these species into extinction.

Asian pangolins have been historically under greater pressure, and according to the CITES wildlife trade database, the Sunda pangolin has the most recorded cases of trafficking. Pangolin populations in Asia have been greatly reduced, and the focus of poachers is slowly shifting towards African species that are becoming more threatened due to overexploitation. Pangolins have been used as bushmeat and for medicinal purposes in Africa as well, but not on a scale on which they have been exploited in Asia. Many areas in Africa where pangolins live are also areas that have high rates of poverty and inequality. A pangolin sold to poachers means that the person who sold it secured sufficient income to provide for their family, for which they would otherwise have to work for weeks or even months. Profits from pangolin trade are large, and trade routes have been already established through major ports across the world to bring poached African pangolins legally and illegally to Asia.